On September 177, 1949, the SS Noronic while docked in Toronto, Canada suffered a catastrophic fire that killed at least 119 people that ended the golden era of Great Lakes passenger cruise ships.

The SS Noronic was launched in 1913 for the Canadian Steamship Company. It was built for passenger and freight service on the Great Lakes. With five decks and the capacity to hold 800 passengers and 200 crew, and 360 feet (110 meters) long, she was the largest and fastest ship on the Great Lakes when launched. And she had many luxuries that other ships did not have. She had her own ice plant, wireless telegraph, bandstands, restaurants, bars, decks lined with mahogany and lounge chairs upholstered with Spanish leather earning her the nickname Queen of the Great Lakes. With fourteen lifeboats in case of emergency, she was considered quite safe as well after the Titanic sinking. However the only entrances and exits to the ship were on the bottom E deck, a fact that would play a major role in the disaster of 1949

She began a seven-day pleasure cruise of Lake Ontario on September 14, 1949. She was carrying 524 passengers and 171 crew. Most of the passengers were American and only twenty Canadians. This voyage would be the last voyage of the season as the ship would be laid up for winter. The captain for this voyage was Wiliam Taylor. Pulling into Toronto Harbor on September 16, she docked at Pier 9 at 7 pm and was scheduled to depart the following day. Many passengers and crew, including the captain, spent the evening in Toronto. Most passengers had returned to the ship before the fire broke out. Only fifteen crew members were aboard the ship that night as many had gone ashore to be with family or friends.

Around 2:30 am (some sources say 1:30 am) passenger Don Church saw smoke on C deck and followed the smell to a locked linen closet. After finding smoke coming from it, he informed bellboy Earnest O’Neill. O’Neil did not raise alarm and instead went to the steward’s office on D deck to get the keys. Upon opening the closet, fire exploded into the hallway spreading quickly. Church ran to get his family. Meanwhile O’Neill and another bellboy along with another passenger attempted to put out the fire. Unfortunately, the fire equipment did not work. He notified Captain Taylor of the fire, and the ship’s whistle was ordered to be blown. Unfortunately, either because of the fire or some other reason, the whistle only gave one blast. By 2:38 a.m., half of the ship’s decks were ablaze and noticed by people ashore alerting the fire department. However, no ship officer or crew member called them. Additionally there was no attempt by the crew to awaken the sleeping passengers.

Donald Williamson, aged twenty-seven, was the first rescuer. He had just come off a late shift and, as a former freighter deckhand, wanted to see the Noronic. He arrived just as the whistle sounded and could see the fire was spreading. He could also see people were frantically trying to get off the ship and jumping into the water. Acting quickly, he moved a large painters’ raft to the port bow and was able to pull people from the water onto the raft. Two police constables who arrived on the scene saw the ship ablaze and encountered survivors in shock and suffering from injuries and burns. Constable Ronald Anderson stripped off his uniform and assisted Williamson on the raft. Fireboats soon arrived to help rescue people in the water. Firefighting equipment arrived at the dock along with ambulances and other police to assist survivors and put out the raging fire.

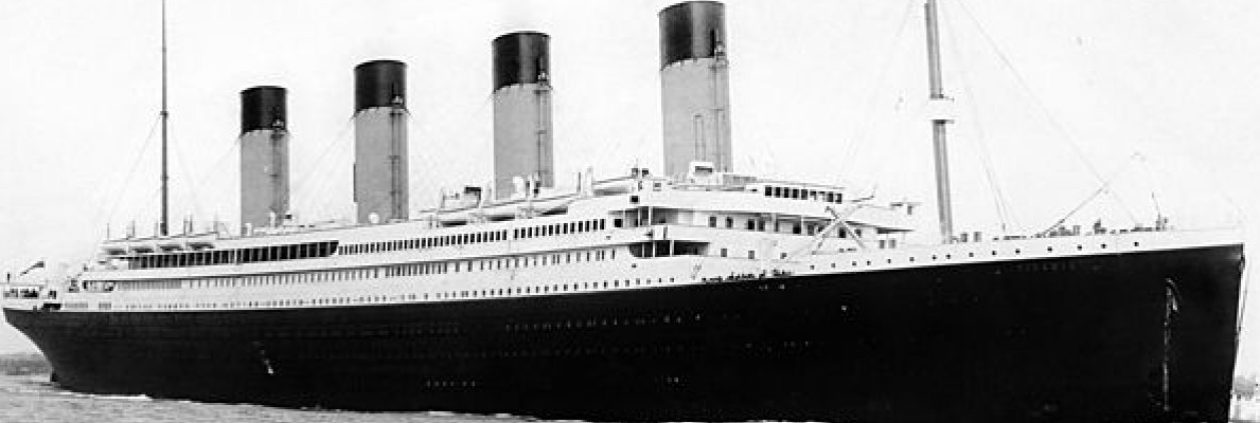

Photo by Norman James, September 17, 1949

Public Domain in US/Canada via Wikimedia Commons

Aboard ship, people were desperate to get out. Portholes were broken by either crew members or passengers to get off the ship. Since the crew had failed to awaken the passengers, most only found out something was wrong when they heard screaming and running in the corridors. With most of the stairwells on fire, few could reach E-deck to escape using the gangplanks. Panic ensued and many were trampled to death. Many used ropes to climb down or to jump into the water. Those trapped on the upper decks–some on fire–jumped to the pier below and died. Others were unable to escape their cabins as the fire consumed the ship rapidly.

Unknown Author

City of Toronto Archives via Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain US/Canada

Attempts to get people off by rescue ladders were not always successful. One ladder was extended to the B deck and was swamped with passengers causing it to snap in two resulting in them being rescued by a lifeboat. Other ladders to C deck were successful and held up as people were able to get off. Despite a tremendous amount of water used to fight the fire, it was quickly realized that the fire would not extinguish. The high amounts of water used though, temporarily caused the ship to list to the pier resulting in firefighters having to retreat until it corrected itself.

By 5 am, the fire had gone out and an astonishing 1.7 million gallons of water had been used by 37 hoses. The ship was cool enough by 8 am to be boarded. Firefighters and others accompanying them found gruesome scenes. The fire burned so hot that instead of corpses they found mostly skeletons with little, or no flesh left. Some were found embracing each other while others were found in their beds. Identification of the remains proved difficult and a new technique, dental forensics was used. Additionally, all the glass fittings were melted, steel fittings warped, and only the bow stairwell survived. Due to a lack records, the exact death toll is unknown, it is estimated between 119-139 may have died, Suffocation was the main cause of death for most, followed by severe burns, being trampled to death in the corridors, jumping to the pier, and one drowning. Initially it was 118 dead by one crewmember would die later from burns suffered on her body bringing the estimated death toll to 119.

Public Domain

The disaster was well covered in the Toronto newspapers and on the American side as well since most of the passengers were American. The question everyone wanted answered was simple: how did this happen? The answers came from the official inquiry that took place later. Investigation showed that the fire had started on the linen closet on C deck and spread rapidly when it was opened by the bellboy. What started the fire is uncertain. A report that some laundry staff were seen smoking near the linen closet led some to believe that a carelessly dropped cigarette was the cause. Interviews of the crew members did not confirm this. Canadian Steamship believed it was arson. Another one of their ships a year later would have a similar fire in a linen closet but it was contained, and no loss of life occurred. The inquiry found that several major issues contributed to how the fire spread so quickly and was so hot. The mahogany wood deck linings had been coated with lemon-oil which the flames fed upon. Additionally, the structure of the ship-as the ship decks were placed close together-spread the fire fast. Improperly maintained fire equipment and extinguishers meant little water could be used on the ship to put it out.

The crew failed to alert the passengers as most were asleep. The one blast of the ship’s whistle before it died was not enough. Many did not know how serious the situation was until they were awakened by noise in the corridors. Some of the crew just fled rather than assist. The lack of clear exit signage and what to do was another factor. Passengers had to make their way down, if they could, to E deck where two planks were available to exit the ship. The rapid movement of the fire made that difficult and later impossible leading to mass panic. Without other exits, many were simply trapped forcing them to find whatever means they could. The fact that the crew mostly abandoned the ship and never had any emergency drills brought condemnation down on both the line owner, Canadian Steamship Lines, and Captain Taylor. Taylor had his master’s license revoked for a year; he would resign before it was made active. The company was sued in court and ended up paying out over two million Canadian dollars.

New regulations were enacted by both Canada and the United States to ensure this would never happen again. Ship design was altered, and new safety regulations were put in place regarding the use of flammable materials aboard passenger ships. Many ships were taken out of service as the cost of retrofitting was too high. The days of the Great Lakes luxury cruises came to an end as a result. With fewer passengers, there was not much profit anymore. Knowing that Canadian Steamship had allowed ships to sail without properly maintained fire equipment and a crew that did nothing to help the passengers, all contributed to the demise. By late 1960’s the last of these old passenger cruise ships were retired from service never to return.

As for the Noronic, it was partially disassembled at the pier and the rest of it towed away to be scrapped. A memorial was erected in the cemetery were many were interred and a memorial plaque put up near where the disaster had occurred. It remains to this day one of the deadliest fires in Toronto history.

Photo: Nick Number, 9 September 2024

Wikimedia Commons

Sources

Bipin Dimri, “The SS Noronic: Death in Toronto Harbor,” Historic Mysteries, last modified December 29, 2023, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.historicmysteries.com/history/noronic/30544/.

By CraigBaird, “The SS Noronic Fire,” Canadian History Ehx, May 27, 2025, https://canadaehx.com/2025/05/27/the-ss-noronic-fire/.

Mike Filey, “THE WAY WE WERE: 119 Tragically Killed in SS Noronic Inferno 70 Years Ago,” Toronto Sun, last modified September 21, 2019, accessed September 15, 2025, https://torontosun.com/opinion/columnists/the-way-we-were-119-tragically-killed-in-ss-noronic-inferno-70-years-ago.

Brennan Doherty Staff Reporter, “September 17, 1949: S.S. Noronic Burns,” Toronto Star, September 17, 2016, https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/september-17-1949-s-s-noronic-burns/article_46ba351c-ad2f-5f3b-954e-74a54589c89f.html.

Chris Bateman, “The History of the S.S. Noronic Disaster in Toronto,” blogTO, August 8, 2020, https://www.blogto.com/city/2012/09/a_brief_history_of_the_ss_noronic_disaster/.

Ontario Heritage Trust, “Noronic Disaster, The,” Ontario Heritage Trust, last modified February 10, 2023, accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/plaques/noronic-disaster.

“Noronic Disaster Historical Plaque,” accessed September 15, 2025, https://torontoplaques.ca/Pages/Noronic_Disaster.

“Steamship Noronic Memorial (Unknown-1949) – Find A…,” accessed September 15, 2025, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10440/steamship_noronic_memorial.

Wikipedia contributors, “SS Naronic,” Wikipedia, last modified August 21, 2025, accessed September 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Naronic.