1912

Public Domain va Wikimedia Commons

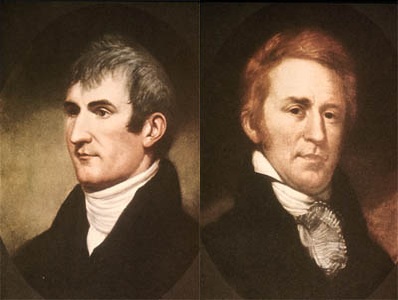

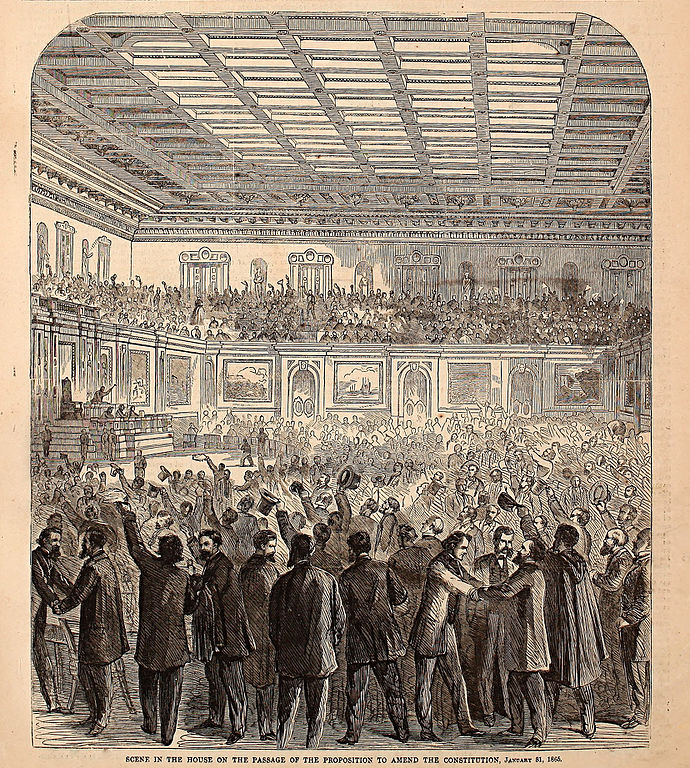

On 2 July 1776, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution that formally declared that American colonies independent of Britain. A final document had to be created explaining the reasons. A committee of five composed of John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Morris, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson worked on a draft form for the Congress to approve. On 4 July 1776 the Declaration of Independence was published. Although John Adams believed 2 July would be remembered for generations, it would be the day the Declaration was published that would be remembered.

Public Domain

It would be spread in July and August in a variety of ways. It was published in newspapers throughout the American colonies. It was spread via word of mouth by horseback and by ships. Newspapers published the Declaration and was read aloud for people and troops serving the Continental Congress. It was also sent to Europe as well. The Declaration clearly spelled out the reasons for the split and roused support for the American Revolution. It was a shocking document read in London and in other capitals. For it laid out clearly and precisely the reasons why a people could, and under the proper circumstances, rise up and replace their government with something better.

Thomas Jefferson, one of the principal writers of the Declaration, wanted to convey in a commonsense manner the reasons for the split. He wanted everyone who read or heard it read aloud to know exactly why this had to occur. He drew upon well-known political works in the language he used. His most important goal was to express the American mind against the tyranny of Britain.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any form of government becomes destructive to these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.

The Declaration announced to the world the uniqueness of the American Revolution. This was not like simply toppling a monarch and replacing him with a Cromwell or another king. It was about creating a government that believed and supported civil liberties along with the idea of self-government. A government that ruled with the consent of the governed, and not the other way around which was common in most of the world. The Declaration would become the cornerstone of what the United States would stand for and inspire others around the world to believe in it as well.

Today many are not sure of what happened in 1776 because they were not taught or learned why this occurred. There are those who try to rewrite history to fit their own narrative, often for political or social reasons or causes. The American Revolution occurred because people had become tired and frustrated by a government that was remote to their needs. They were British citizens, and many had families that came from Britain and settled in the colonies. They assumed they had the same basic rights of all English citizens, but the government saw the colonies as a means of revenue to refill their treasury. And they had little representation back in London, unlike there where you had a House of Commons that represented each borough.

When the British imposed taxes and restrictions on the American Colonies, many were disturbed by these actions and began protesting them. Attempts in some small ways of self-governance were met with indifference or hostility. The infamous tax on tea that led to the famous Boston Tea Party (1773). While this act was not celebrated by everyone (John Adams and George Washington, both thought it was wrong), it became a defining act of defiance, and the British took note since 45 tons of tea (worth a lot of money) was destroyed. The British closed down the port, demanded compensation, ended the Massachusetts Constitution, ended elections of public officials, instituted martial law as all courts were moved to Britain, required housing of British troops on private property. And to further snub the local Protestants, French-Canadian Catholics were allowed to worship openly.

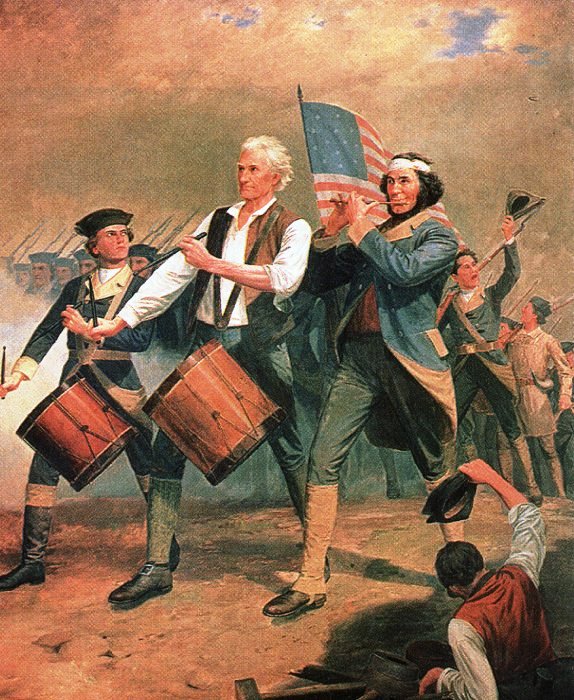

These rules, called the Coercive Acts, led to the First Continental Congress of 1774. Many thought what happened was wrong but this was too far. The British hoped the acts would stop further acts of rebellion but ended up doing the opposite. It brought together people of all levels against the British and further convinced many that they now lived under a tyranny. The First Continental Congress, while disagreeing about the Boston Tea Party, was strongly united against Britain because of the Coercive Acts. In their declaration they formally censured Britain for these acts, imposed a boycott of British goods, declared they had a right to govern themselves, and called on colonists to form militias. For most it came down to a simple word: sovereignty. And so, the Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776, they declared to the world the reasons why they had to formally break with Britain and declare their independence. Those that signed the declaration knew they would become targets, and many did. Some were arrested, imprisoned, or executed. Families were destroyed. Many leaders would lose all their wealth during the war to follow. And it was no sure thing they would win.

Britain was one of the premier powers of Europe at the time, with France being the other. They had a highly trained army and navy against a ragtag group of colonials though some had military experience (like George Washington). And the British showed, along with German mercenary troops, they were indeed not to be doubted. Yet something remarkable did happen. Despite all the odds against them, battles lost, cities taken, and at times appearing hopeless, the Americans did turn it around and show the British that they were determined and resolved in their desire to win. And they did to the surprise and shock of the world. They had defeated Britain and achieved their independence. What came of it was an American republic, distinctly different from anywhere else, where government was set to serve the people and constrained by a constitution, to prevent a tyrant from ruling outright. And the first amendments to this constitution would enshrine and limit those powers they so detested the British had done to them.

Suggested Reading

O’Donnell, P. K. (2017). Washington’s Immortals: The Untold Story Of An Elite Regiment Who Changed The Course Of The Revolution. Grove Press.

Warren, J. D., Jr. (2023). Freedom: The Enduring Importance of the American Revolution.

Wood, G. S. (2003). The American Revolution: A History. Modern Library.

Titanic News Channel is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

On 2 July 1776, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution that formally declared that American colonies independent of Britain. A final document had to be created explaining the reasons. A committee of five composed of John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Morris, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson worked on a draft form for the Congress to approve. On 4 July 1776 the Declaration of Independence was published. Although John Adams believed 2 July would be remembered for generations, it would be the day the Declaration was published that would be remembered.

On 2 July 1776, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution that formally declared that American colonies independent of Britain. A final document had to be created explaining the reasons. A committee of five composed of John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Morris, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson worked on a draft form for the Congress to approve. On 4 July 1776 the Declaration of Independence was published. Although John Adams believed 2 July would be remembered for generations, it would be the day the Declaration was published that would be remembered.