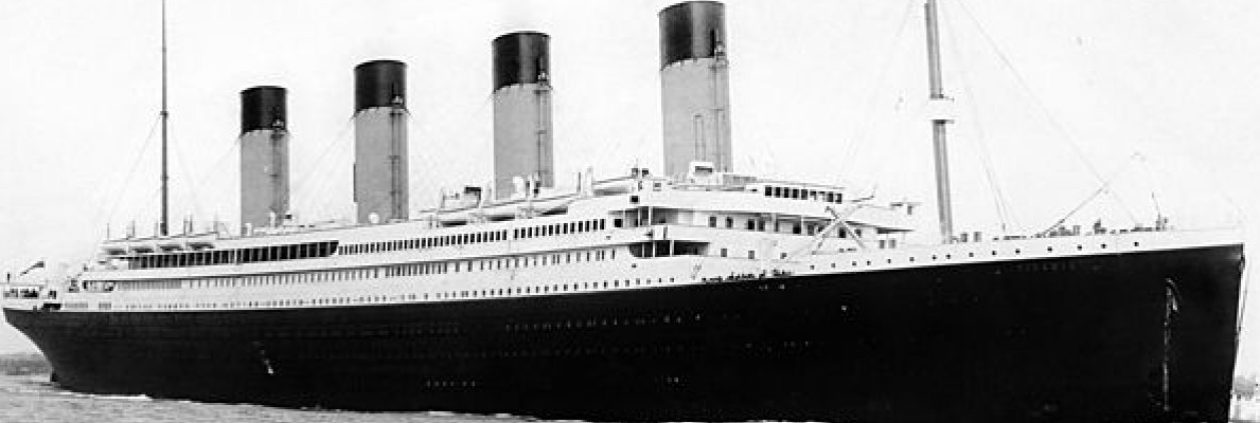

Photo: Greenmars(Wikipedia)

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald sank in Lake Superior on 10 Nov 1975 taking with her a crew of 29. The ship was launched in 1958 and was owned by Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company. As a freighter, the ship primarily carried taconite iron ore to iron works in various Great Lake ports. The ship set records for hauling ore during its career.

On 9 Nov 1975, the Fitzgerald under the command of Captain Ernest McSorley, embarked on her final voyage of the season fron Superior, Wisconsin to a steel mill near Detroit, Michigan. She met up with another freighter, SS Arthur Anderson, while enroute. The next day a severe winter storm hit with near hurricane force winds and waves that reached 35 feet in height. Sometime around or after 7:11 p.m., the Fitzgerald sank in Canadian waters approximately 17 miles from Whitefish Bay near the cities of Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. While McSorley had reported difficulty earlier, his last message was “We are holding our own.”

The cause of the sinking has stirred debate and controversy with competing theories and books on the issue. The various theories are:

(1) Inaccurate weather forecasting. The National Weather Service forecast had said the storm would pass south of Lake Superior but instead it tracked across the eastern part, exactly where the Edmund Fitzgerald and Arthur Anderson were. So they were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

(2) Inaccurate navigational charts. The Canadian charts in use came from 1916 and 1919 surveys and did not include more updated information that Six Fathom Shoal was about 1 mile further east than shown.

(3)No Watertight Bulkheads

The ship did not have watertight bulkheads and more like barges rather than freighters. So a serious puncture could sink a vessel like Fitzgerald while ships that had such bulkheads, even if seriously damaged, had a better chance of survival.

(4)Lack of Sounding and Other Safety Instruments

Fitzgerald lacked the ability to monitor water depth using a fathometer( a device that uses echo sounding to determine water depth). The only way the Fitz could do soundings was using a hand line and counting the knots to measure water depth. Nor was there any way to monitor if water was in the hold or not (some was always present reports suggest)unless it got high enough to be noticed by the crew. However on that night, the severity of the storm made it difficult to access the hatches from the spar deck. And if the hold was full of bulk cargo, it was virtually impossible to pump out the water.

(5)Increased Cargo Loads Meant Ship Was Sitting Lower In Water

The load line had been changed in 1969, 1971, and 1973 with U.S. Coast Guard approval. This resulted in Fitzgerald’s deck being only 11.5 feet above the water when she faced massive 35 foot waves on that day. She was carrying 4,0000 more tons than what she was designed to carry. Which meant the buoyancy of the ship was an issue who fully loaded resulting in reports the ship was sluggish, slower, and reduced recovery time.

(6)Maintenance

The US National Transportation and Safety Board believes that prior groundings caused undetected damage that led to major structural failure during the storm. Since most Great Lakes vessels were only inspected in drydock once every five years, such damage would not have been easily detected otherwise. Concerns have also been raised that Captain McSorley did not keep up with routine maintenance. Photographic evidence indicates the hull was patched in places and the failure of the U.S. Coast Guard to take corrective action is also an issue considering that various things were not properly maintained.

(7)Complacency

Captain McSorley rarely pulled his ship into a safer harbor to ride out a storm. Nor did he heed a warning from the U.S. Coast Guard issued at 3:35 p.m. to seek safe anchorage. Possible pressure from ship owners to deliver cargo on time is considered a factor for some captains like McSorley to ride out storms rather seek safe anchorages. The U.S. Coast Guard Marine Board concluded that complacency is a major factor in what happened to Fitzgerald and generally a problem for Great Lakes shipping. Critics point out the Coast Guard failed in its own tasks of properly requiring those repairs and lacked the means to rescue ships in distress on the Great Lakes.

The wreck was found on 14 Nov 1975 using technology to find sunken submarines. The U.S. Navy dived to the wreck in 1976 using an unmanned submersible. The wreck was found to be in two pieces with taconite pellets in the debris field. Jacques Cousteau dived to it in 1980 and speculated it had broken up on the surface. A three day survey dive in 1989 organized by the Michigan Sea Grant Program was done to record the wreck for use in museum educational programs. It drew no conclusions as to the cause of the sinking. Canadian explorer Joseph MacInnis led six publicly funded dives over three days in 1994 to take pictures. Also that year sport diver Fred Shannon and his Deepquest Ltd did a serious of dives and took more than 42 hours of underwater video. Shannon discovered when studying the navigational charts that the international boundary had changed three times. GPS coordinates showed the wreck was actually in Canadian waters because of an error in the boundary line shown on official lake charts. MacInnis went back to the wreck in 1995 to salvage the bell and it was financed by the Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians. A replica bell and a beer can were put on Fitzgerald. Scuba divers Terrence Tysall and Mike Zee used trimix gas to dive to the wreck and set records for deepest scuba dive on Great Lakes. They were the only divers to get to the wreck without a submersible.

The wreck is now restricted under the Ontario Heritage Act and has been further amended that a license is required for dives, submersibles, side scan sonar surveys and even using underwater cameras in the designated protected area. And they added a steep fine of 1 million Canadian dollars for violating the act.

Fitzgerald was valued at $24 million. Two widows filed suit seeking $1.5 million from the owners and operators of the ship. The owners filed to reduce to limit their liability. However the claims never went to trial as the company paid compensation to the surviving families who signed confidentiality agreements. It is believed the owners and operator wanted to avoid a court case where McSorley was found negligent as well as the operator and owner. Changes to Great Lakes shipping did occur such as requiring fathometers in ships above a certain tonnage, survival suits, locating systems for ships (LORAN originally now GPS), emergency beacons, better wave predictions, and annual inspections of ships in the fall to inspect hatch and vent closures.

Annual memorials take place though the one made famous by Gordon Lightfoot, the Mariners Church in Detroit, now honors all who perished on the Great Lakes.

Sources:

1. SS Edmund Fitzgerald(Wikipedia)

2. Mariners Church, Detroit, Michigan

3. Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum

4. Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

5. The sinking of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald – November 10, 1975 (University of Wisconsin)

6. National Transportation Safety Board:Marine Accident Report

SS Edmund Fitzgerald-Sinking In Lake Superior (4 May 1978)

7. Marine Historical Society of Detroit